A common observation can be made with newcomers to Vim; plethoras of plugins transform the minimal editor into something vaguely resembling an IDE. Often, it’s not long until “autocompletion” comes up, and how Vim’s apparent lack thereof spawns posts titled “I can’t get YouCompleteMe to work”…

If that sounds uncanny, I speak from a similar experience—like others before me,

I too tried YouCompleteMe, Eclim, Tern, Jedi… you may be unsurprised to know

I uninstalled the lot, committing instead to learn Vim’s built-in

autocompletion. If you take one thing from this post, please let it be to study

:help ins-completion—<C-x><C-l> still provides what I need 9 times out of

10.

But then came Language Servers.

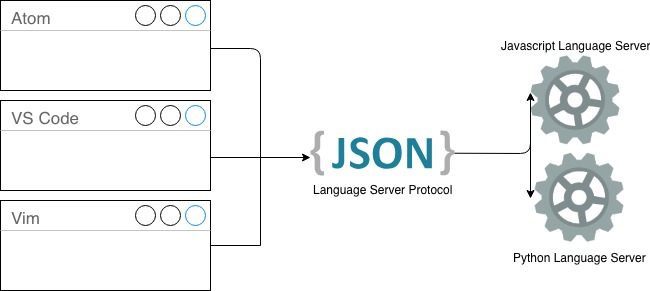

Whilst developing VS Code, Microsoft introduced the Language Server Protocol (LSP): an interface between servers and text editors in which the servers provide text-editors with autocomplete capabilities (et. al). These LSP-compliant servers—or Language Servers—are different to traditional autocomplete engines in that they are vendor agnostic; they run as stand-alone programs on a host machine instead of being bundled within text-editors.

In practice this means you can install one Language Server, and have many LSP-compliant text-editors use it. The inverse of this relationship means you can install one LSP plugin in your text-editor, and profit for as many Language Servers you have installed:

Installing, configuring & using Language Servers.

Hopefully, this is starting to sound feasible to you—at least conceptually. In my experience, the least documented/intuitive part of Language Servers is installing, configuring and using them. Take for instance this configuration advertised by the autozimu/LanguageClient-neovim plugin:

let g:LanguageClient_serverCommands = {

\ 'rust': ['~/.cargo/bin/rustup', 'run', 'stable', 'rls'],

\ 'javascript': ['/usr/local/bin/javascript-typescript-stdio'],

\ 'javascript.jsx': ['tcp://127.0.0.1:2089'],

\ 'python': ['/usr/local/bin/pyls'],

\ }

Without digging into the source code, this configuration suggests you can:

- Boot up a Language Server by pointing to a binary on the host, or

- Connect to a Language Server that is already listening on a socket.

Let’s explore the two options now.

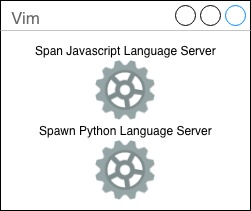

Option A: Boot up a Language Server.

This is probably the quickest way to get started—you can install a JavaScript

Language Server via $ npm install -g javascript-typescript-langserver, and

then configure LanguageClient-neovim to use the global

javascript-typescript-stdio binary. Boom, job done for JavaScript.

Want LSP for Python, too? Sure, $ pip install python-language-server and point

LanguageClient-neovim to the global pyls… Alright… now

imagine repeating this process for multiple languages; C#, Java, Go, Ruby,

Bash… Okay… Now what if you have multiple machines—say a laptop for

personal use, and another one for work? Well, installing them all over again is

getting kinda tedious… But shit—the different laptops have installed the

Language Servers into subtly different locations, and now your shared

dotfiles are broken.

Option B then?

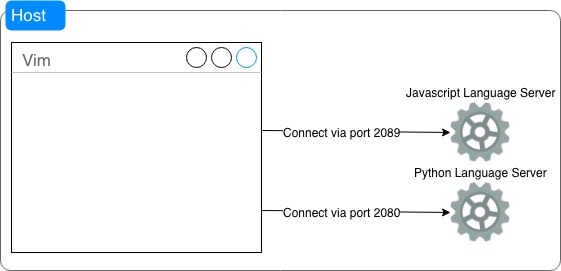

Option B: Connect to a Language Server via TCP.

Alright this requires a little upfront effort, but with it I have integrated LSP into my everyday workflow—something I’m a stickler for. The key difference is we shift responsibility for the Language Server’s life-cycle to the host machine, as opposed to the LanguageClient-neovim plugin. Put another way, when we are able to guarantee a Language Server is listening on a specific port, this provides a contract needed to decouple Vim from machine-specific idiosyncrasies:

# Option A: Vim is coupled to location of Language Server

# binary, As the path can change, the config is brittle!

let g:LanguageClient_serverCommands = {

\ 'javascript': ['/usr/local/bin/javascript-typescript-stdio']

\ }

# Option B: So long as a Language Server is listening on

# port 2089 somehow, Vim doesn't care.

let g:LanguageClient_serverCommands = {

\ 'javascript': ['tcp://127.0.0.1:2089']

\ }

To make the host machine responsible for the Language Servers, start the

Language Servers as system daemons. For example—given I run macOS—I copied a

JavaScript Language Server plist into the

~/Library/LaunchAgents directory, and executed the $ launchctl load

~/Library/LaunchAgents/js-lsp.plist command. This ensures the Language Server

will listen on port 2089 when I log in, and shut down when I log out. Neat

right?! If you want another example, here’s a plist for the

Python Language Server that listens on port 2090.

Automate, automate.

I’ll wrap this section up by imploring you to automate Language Server

installation. Daemon files (such as the *.plists) are usually text files,

which makes them ripe for committing and installing with your dotfiles. The

astute reader may have already noticed I embed my plist files into Homebrew

Formulae, which means I can commit them into a

.Brewfile, execute $ brew bundle install and chill out whilst

Homebrew install the Language Servers as system daemons. Easy life!

If you want to try this out for yourself, run the following commands:

# Install the formula.

brew tap kieran-bamforth/repo

# Install the JavaScript language server on port 2090.

brew install kieran-bamforth/javascript-typescript-langserver

# See that it is running!

brew services ls

Augment Vim with your new Language Server.

Thanks for sticking with me so far, the hard effort will pay off. All we have to do now is to configure some keyboard shortcuts for the Language Server—you’ll be well on your way!

Before rushing off to invent a new shortcut, it’s always worth asking can we

augment Vim’s existing functionality?. Take for instance, the jump to a

symbol declaration feature provided by Language Servers… it lines up with

Vim’s go to local declaration feature nicely, don’t you think?. Let’s remap

gd to take advantage of this:

nnoremap <buffer> <silent> gd \

:call LanguageClient#textDocument_definition()<CR>

This key-binding works nicely until we use gd in a buffer that is not

associated with a Language Server—Vim will do nothing. This scenario is a good

candidate for graceful degradation—that is—if the Language Server does

nothing, fall back to Vim’s built in functionality. Here’ an iteration of the

previous snippet that takes into account graceful degradation:

autocmd FileType * call LanguageClientMaps()

function! LanguageClientMaps()

if has_key(g:LanguageClient_serverCommands, &filetype)

nnoremap <buffer> <silent> gd \

:call LanguageClient#textDocument_definition()<CR>

endif

endfunction

Can you think other Vim-features worth augmenting? The “hover” feature from

Language Servers aligns pretty nicely with Vim’s “keyword lookup” (help K),

for instance. Please share yours in the comments!

Vim + Language Server Protocol—in 2019.

I introduced the concept of Language Servers by talking exclusively about the LanguageClient-neovim plugin—but it’s well worth remembering there are others out there (vim-lsp, ALE, etc). In fact, I extended ALE to use Language Servers before moving onto LanguageClient-neovim.

Eagle-eyed readers may notice the aforementioned ALE configuration uses the same ports as successive LanguageClient configuration. This is no accident! In fact, I think this empirically proves Microsoft’s vision for the LSP; I was able to upgrade my text-editor easily independently of any autocomplete engines—just check out how easy it was.

Composing small, sharp tools together is a creative task; the aggregates of which go can solve unlimited problems. It is no accident we can pipe the output of one shell command into the next, for the UNIX philosophy states “the universal interface is text”. It is by agreeing and complying to interfaces our tooling can thrive—and this is precisely what LSP provides for our text-editors in 2019.